|

| A few of our Kiva borrowers |

Shortly before leaving on a trip to Eastern Europe in 2007, my husband and I did something that would baffle any traveler who’s been approached at a train station in Rome or Paris by women in flowing skirts, cradling babies in their arms and begging for coins.

We loaned money to Gypsies through non-profit start-up called KIVA which was experimenting with taking micro- financing - the making of small loans to entrepreneurs in poor or developing countries - to a new level by using a social networking platform to connect borrowers and lenders in far-away places.

Our new business partners were Diana Beleva, 26, a traveling sock saleswoman; and her brother Todor Belev and his wife, Silvia, who made a living selling firewood in the Balkan mountain town of Sliven, Bulgaria. Our loans of $25 each were "crowdfunded" along with others to produce a pool of money large enough to help Diana buy more socks, and Todor and Silvia to buy a chain saw to cut more firewood.

After traveling to Sliven an arranging through a Peace Corp volunteer to meet up up with our Bulgarian friends in-person, we continued to make loans through KIVA to people in other countries. Fast-forward to 2022. Our "portfolio" shows how our original two $25 Bulgarian loans, plus four others made over the years (a total of $150) were paid back and rolled over to fund 63 loans in 16 countries worth a total of $1,575.

Neither Kiva nor lenders like us collect any interest (administration costs are funded by donations). Borrowers pay interest to Kiva’s partners — non-profit micro-financing field partners around the world — who identify entrepreneurs in need. A payment schedule is set up, and once the loan is repaid, the lender can decide to collect the money or use the funds to make another loan. KIVA estimates its default rate is around 4 percent on the $1.6 billion in loans it has helped fund in 77 countries.

Pictures of borrowers along with descriptions of their businesses appear on Kiva's website. I love looking back on some of the people, and recalling their stories, especially during Covid when memories stand in as a substitute for travel.

|

| Diana Beleva at home in Sliven, Bulgaria |

In their T-shirts and ball caps, our Bulgarian friends looked no different from most Europeans. But they were Roma, an Eastern European ethnic minority commonly known as "Gypsies." Many settled in towns like Sliven, the sock-manufacturing empire of the Soviet bloc until the communist government fell in 1989 and most of the factories closed.They wanted to work, send their children to school and build a future, but no bank would loan them money at anything close to a reasonable rate. With interest rates between 30 and 40 percent, the alternatives for most Roma were loan sharks charging100 percent or more.

Diana became one of 35 business owners in Slevin — bakers, barbers, musicians and others — to benefit from Kiva loans. Thirty-two lenders in all, including an Oregon author and a Seattle bus driver, chipped in various amounts to help Diana raise $1,000, money she paid back over the next 12-18 months at 10 percent interest to a micro-credit organization funded by Hungarian-American businessman George Soros. She used the money to buy more socks, replace her hand-lettered cardboard sign and buy an awning to replace the plastic tarp she used at outdoor markets when it rained.

“Here in Bulgaria, you could not find anyone to help you out like this,” she told me when we met.

I don't know what became of Diana or the couple who made a business selling firewood, but their stories were enough to encourage me to continue making loans through KIVA.

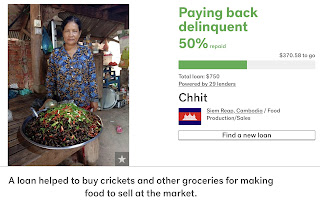

I first focused on entrepreneurs in Cambodia where, after taking a "Reality Tour" with the San Francisco-based non-profit Global Exchange, we felt a bond with people in struggling rural villages.

One of my favorites is a $25 loan to a widow in Siem Reap named Chhit who has a business cooking and selling fried crickets at the local market. Chhit fell behind on her payments during Covid, but is catching up and has now paid back half of her $750 loan.

I try to look for ways to make loans in other countries where we plan travel. Before visiting Peru in 2018, I found the Los Amigos (Friends) group on KIVA. One of the members, Filipa, 51, was seeking a loan to buy seeds and fertilizers to grow corn and potatoes on a farm in Cusco. She raised $1,850 from 58 lenders and has since paid back the entire amount.

With economic problems fueling immigration from Central America into the U.S., I shifted my focus to making loans to entrepreneurs in Guatemala, Honduras and Nicaragua. Many are women who have decided to stay and make it in their own countries. They deserve our support.

She and six other women in the group attend monthly meetings where they gather to make their loan payments and participate in educational training focused on raising their self- esteem.

They recently paid off a $3,300 loan funded by 99 lenders. No wonder they look proud.

I love it, when like Paul Harvey used to say, I get the rest of the story! I remember your loans and this is such a wonderful report. Thanks for this one, Carol.

ReplyDeleteThank you for sharing beautiful content.

ReplyDeletewordpress

blogspot

youtube

កាស៊ីណូអនឡាញ